The title vidyadhara, bearer of awareness, is accorded only the greatest of vajrayana masters. The vidyadhara Jatsön Nyingpo was one of the greatest tertöns of the Seventeenth Century. Jatsön Nyingpo’s revelations continue to be widely practiced throughout the Himalayan region, and even in other parts of the world.

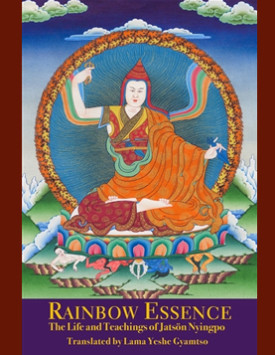

Rainbow Essence: The Life and Teachings of Jatsön Nyingpo

by Jatsön Nyingpo

translated by Yeshe Gyamtso

2018

ISBN: 978-1-934608-53-1

Freench flaps

5.5 x 8.5 in. 192 pages

Buy Now

Translator’s Introduction

The title vidyadhara, bearer of awareness, is accorded only the greatest of vajrayana masters. The vidyadhara Jatsön Nyingpo was one of the greatest tertöns of the Seventeenth Century. A tertön is a revealer of terma: concealed teachings and other sacred objects. Jatsön Nyingpo’s revelations continue to be widely practiced throughout the Himalayan region, and even in other parts of the world.

His teachings spread throughout many branches of the Nyingma, Kagyu, and other Tibetan Buddhist schools, and formed part of the spiritual practice of many great teachers, including Jamgön Lodrö Taye and the Fifteenth Karmapa Kakhyap Dorje.

His collected revelations are usually referred to as the Six Volumes of Jatsön Nyingpo. These include the Very Profound Embodiment of the Three Jewels; the Peaceful and Wrathful Deities: The Essence of the True Meaning; Mahakarunika: The Self-Liberation of Lower States; Amitayus: A Vajra of Meteoric Iron That Brings All Siddhis; Hayagriva, Vajravarahi, and the Wish-Fulfilling Jewel; and the Glorious Intersex Protector. Each of these six cycles has many parts; included with them are his other revelations, such as Gampopa’s Secret Path of Gurusadhana, the Eight Dispensations: The Essence of Siddhi, and the Black Hum Heart Essence.

In addition to his revelations, Jatsön Nyingpo wrote commentaries, essays on Tibetan religious history, and a number of memoirs. These include accounts of some of his previous lives, his recollections of being with his teachers, and what he classified as his fourfold memoirs.

As readers will discover, he called his actual autobiography his Outer Memoir. It is translated in its entirety in this book. Readers will also discover that he finished it and then added more to it several times; I have called these sections Chapter One, Chapter Two, and so on, and indicated the years they deal with. His last entry was while he was in his fifty-seventh year, in 1642 C.E.

Jatsön Nyingpo called his collected songs and written advice his Inner Memoir. This is not translated here, but many examples of his songs are to be found in these pages as they are also part of the autobiography itself.

His Secret Memoir is an account of some of his visions and visionary dreams. I have translated part of this: his account of a dream he had upon completing his intensive practice of the Embodiment of the Three Jewels.

His Very Secret Memoirs are twofold: one is an account of a prophecy he received concerning his monastery in Kongpo in southern Tibet, Bangri Tashi Öbar; the other is an account of how he revealed terma. I have not translated either of these here as Jatsön Nyingpo made it extremely clear that they were not intended for public dissemination. However, I have included an account of the discovery of the Embodiment of the Three Jewels written by Dakpo Norbu Gyenpa, the rebirth of the renowned Dakpo Tashi Namgyal. Norbu Gyenpa was one of Jatsön Nyingpo’s main gurus, and also became one of his principal dharma heirs. This account agrees in every respect with Jatsön’s own.

There is no cause to doubt the year of Jatsön Nyingpo’s birth, 1585 C.E., but there are discrepancies among even the best sources regarding two equally significant dates: the year of his discovery of the Embodiment of the Three Jewels, the first of his revelations and even now the most commonly practiced; and the year of his death.

Jamgön Lodrö Taye, in his Lives of the Hundred Tertöns, gives the year 1620 C.E. as the year of this revelation. However, several editions of Norbu Gyenpa’s account, written during Jatsön Nyingpo’s life, date it twelve years earlier: 1608. Both were Monkey years, and Jatsön Nyingpo states clearly in his Very Secret Account of My Revelations that this revelation occurred during a Monkey year; he just doesn’t say which one.1608 was an Earth Monkey year; 1620 a Metal Monkey year.

In a colophon to his terma the Essence of the True Meaning, which was discovered at the same time and place as the Embodiment (but not disseminated until much later), the tertön gives the year of its discovery as the Earth Monkey year. Nevertheless, as His Holiness the Seventeenth Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje remarked to me a few years ago, 1608 sounds too early and 1620 too late.

What His Holiness was referring to is the fact that by his own account Jatsön’s many years of solitary retreat only began in 1608, his twenty-fifth year. On the other hand, we know based on Norbu Gyenpa’s account that he taught the Embodiment at Daklha Gampo, Gampopa’s seat, in or before 1623. Since we also know that, by Jatsön’s account, he practiced the Embodiment secretly for years before teaching it, and since specific omens were required before he could disseminate it, a mere three years between discovery and dissemination sounds too short.

Here, in translating Norbu Gyenpa’s account, I will use the date 1608, since three out of the five editions of it that I have consulted give that date: the Earth Monkey year, as opposed to the Metal Monkey year.

In his Lives of the Hundred Tertöns Jamgön Lodrö Taye gives the year of Jatsön’s death as the Fire Monkey year, 1656, his seventy-second year. Numerous other Tibetan and English-language sources written since and drawn from Lodrö Taye’s account have given the same date. However, in his account of Jatsön’s final days, which I have translated here, Tsele Natsok Rangdröl (whom we believe to have been a previous life of Jamgön Lodrö Taye), who knew Jatsön well and was one of his most eminent disciples, clearly gives the year of Jatsön’s death as 1646, his sixty-second year. Therefore, in translating Tsele’s account, I have translated his statement that Jatsön Nyingpo died in the Fire Dog year, 1646, without alteration.

The Seventeenth Century was a time of turbulence in Tibet. In particular, Tibet became swept up in the wars between opposing factions among the many Mongolian tribes because of the allegiance of various Mongolian leaders and tribes to different traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Of principal importance to Jatsön Nyingpo’s account of his later life is the conflict between Gushri Khan, the leader of the Koshuts, and Choghtu Khong Tayiji, a Khalkha prince. In 1637 Gushri Khan successfully invaded and conquered Amdo, in present-day Qinghai, and defeated and killed Choghtu. Subsequently, in 1642, Gushri Khan invaded central Tibet and defeated the powerful king of Tsang, allowing the unification of Tibet under the theocratic government that continued to rule that country until the disastrous events of the mid-Twentieth Century. To understand Jatsön Nyingpo’s reaction to this conflict it is helpful to remember that Choghtu Khong Tayiji and the king of Tsang were both patrons of the Karma Kagyu tradition, with which Jatsön himself was closely affiliated.

Included in this book are four translations: the complete autobiography; Tsele’s account of Jatsön’s final days; Norbu Gyenpa’s account of the revelation of the Embodiment of the Three Jewels; and Jatsön Nyingpo’s own account of his dream journey to Guru Rinpoche’s realm, an extract from his Secret Memoir. For the reader’s convenience, these four translations are called Part One, Part Two, and so on.

It has taken me a shameful number of years to complete this translation, but the fact that it has been finally completed is entirely due to the encouragement and blessings provided by the following people:

His Holiness the Seventeenth Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje, who has blessed this project in many ways; the Lord of Refuge Kalu Rinpoche, Karma Rangjung Kunkhyap; Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche; and Lama Norlha Rinpoche.

Peter van Deurzen and Maureen McNicholas have made this book possible by publishing and editing it. Maureen, in particular, is much more than an editor or publisher; it would be more apt to call her a creator of books. Her standards for both editing and the creation of books in general would improve the quality of books everywhere were they universally implemented.

Without the Buddhist Digital Resource Center, founded by the eminent Dr. Gene Smith, I would have had no access to multiple editions of the texts translated here, and therefore no way to compare different editions in order to determine their accuracy. Beyond that, the Buddhist Digital Resource Center gives so many of us, Tibetans and non-Tibetans alike, ready access to countless Tibetan books that would otherwise be unavailable, and in many cases would probably no longer exist.

Whatever good there is in these translations is entirely due to the above mentioned people. Any and all errors are mine alone.

Yeshe Gyamtso