Uniquely attuned to our present world, the Karmapa gives clear and wise teachings on key issues of our times – the environment, social responsibility, and working with our emotional afflictions. He brings a fresh perspective on how to meditate and encourages us to take the path of compassion, engaging in actions that benefit others. The Karmapa brings forth a profound message in simple and accessible language with an authenticity that connects him to everyone he meets as he opens out the treasures of Buddhism for modem times.

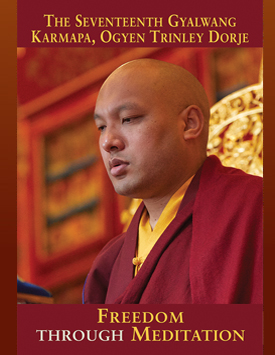

Freedom through Meditation

By the Seventeenth Gyalwang Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje

(Canadian talks 2017)

Preface by the Seventeenth Gyalwang Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje

Translators: David Karma Choephel, Tyler Dewar, Michele Martin (and editor)

Cover photo by Robert Hansen-Sturm

Fall 2018

ISBN 978-1934608-5-79

Paperback

5.5 x 8.5 in., 160 pages

Buy Now

Contents

Preface: The Seventeenth Gyalwang Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje

Introduction (by Translator)

Chapter One: Love and Compassion Are Critical to Our Lives

Chapter Two: Transforming Disturbing Emotions, A Dialogue among the Three Major Traditions of Buddhism

Chapter Three: Ground, Path, and Fruition — Session I

Chapter Four: Ground, Path, and Fruition — Session II

Chapter Five: Finding Freedom through Meditation

Chapter Six: Compassion Is More Than a Feeling

Chapter Seven: Mindfulness and Environmental Responsibility

Chapter Eight: Compassion Does Not Stop at Empathy, Excerpts from an Avalokiteshvara Initiation

Chapter Nine: Interconnectedness, Our Environment and Social (In)equality: The Gyalwang Karmapa and Professor Wade Davis in Dialogue

Chapter Ten: Working with Disturbing Emotions

The Practice of Akshobhya

Chapter Eleven: Putting the Teachings into Practice

Questions and Answers

Preface: The Seventeenth Gyalwang Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje

In the summer of 2017, I was fortunate to be able to visit Canada for the very first time, traveling the breadth of this vast land to Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver. In so doing, I was following in the footsteps of the Sixteenth Gyalwang Karmapa, Rangjung Rigpe Dorje, who visited Canada in the 1970s. I had the chance to see for myself the places where he had been. It gave me great joy to witness how the foundations he had laid so many years ago for the flourishing of the Buddhist Dharma have been preserved into the twenty-first century. One of my principal aims in visiting Canada was to meet with the Tibetan diaspora, especially in Toronto, which is the largest Tibetan community in North America. I was also delighted to have a chance to visit many of the Dharma centers, where I met and talked with members, gave teachings and empowerments, and was able to deepen Dharmic connections with students. The itinerary included several public events such as meetings with Canadian parliamentarians in Ottawa and the state legislature of Ontario, a dialogue with Buddhists from other traditions, and a discussion with Professor Wade Davis at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, and it also gave me the opportunity to meet with representatives of the First Nations.

My impression is that Canada is a truly multicultural society. Throughout my stay in Canada, I observed the tolerance and respect with which the different peoples treat each other’s cultural and religious traditions. In my view, this is the reason why Canadian people from so many different backgrounds can live and work together in harmony and has proven a very supportive environment for Tibetans and Tibetan culture.

I would like to thank Khenpo David Karma Choephel and Tyler Dewar, who were my translators on the tour and whose translations provided the basis for this book, Freedom through Meditation. Finally, I would like to thank Michele Martin. This book would not have existed without her dedicated effort in translating, checking, and editing the compilation. I welcome its publication and hope that it will be of interest and bring benefit to many.

The Seventeenth Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, June 18, 2018

Introduction

For one historic month, from May 29 to June 29, 2017, His Holiness the Seventeenth Karmapa traveled and taught throughout Canada for the first time. From another perspective, however, this was a return visit after a forty-year absence, for he was following the path of his predecessor, the Sixteenth Karmapa, Rangjung Rigpe Dorje, who had made teaching tours to Canada in 1974, 1977, and 1980. This time the Karmapa visited Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver. Wherever he stopped, he met with large groups of Tibetans who were delighted to welcome him to the multicultural world of Canada. Attuned to our present world, he gave teachings that covered the environment, social responsibility, working with our afflictions, and instructions on how to meditate. He visited parliament and engaged in lively dialogs with monks from the Theravadin and Mahayana traditions as well as a professor from the University of British Columbia. The Karmapa also offered five empowerments, met with three major Tibetan communities in Toronto, Calgary, and Vancouver plus MPs from the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, and blessed temples and Dharma centers of various traditions.

The eleven teachings selected for this volume represent his major talks and excerpts from an empowerment. Taken as a whole, they give all the elements needed for a fulfilling Dharma practice, from the panorama of the entire path, to subtle teachings on working with all aspects of our minds and emotions while also giving heartfelt encouragement to take the path of compassion and engage in activities that benefit others. Throughout his talks, the Karmapa pointed to the interconnection between meditation and social involvement: in the seventh chapter he links mindfulness to taking responsibility for the environment, and in the last chapter he responds with an open heart to specific questions about meditation and practice in the world.

The Karmapa’s style of teaching is unique, and a few comments might be helpful to illustrate a deeper level meaning, so we are not mislead by what appears closer to the surface. In Tibetan writing, there is something that could be called a literary device, which is known as “rejecting arrogance” or “humility” (kengpa pongwa, khengs pa spong ba). In this mode authors deflate any chance of being puffed up about their positive qualities. One of the most famous examples can be found in the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva by the master Ngulchu Thogme. After a brilliant summary of the bodhisattva’s path, he writes:

For an inferior intellect like mine it is difficult To fathom the vast activity of a bodhisattva, So I pray that genuine masters will tolerate All the defects here, the contradictions, irrationalities, and so forth.

This art of putting oneself down is not limited to literature, but permeates the whole of Tibetan culture, in which humility is an attribute expected not only of realized masters and brilliant scholars, but from everyone, especially those who have accomplished something admirable. Since the opposite is usually the case in our contemporary world, it is important not to take the Karmapa literally when he states, for example, “I don’t have much formal meditation experience, so I think it will be very difficult for me to explain meditation today.” He followed this put-down with a classic example of his deadpan humor: “Perhaps the organizers knew this and made meditation the topic of this morning’s talk in order to test me.”

This lowering of himself has the added benefit of making the Karmapa more approachable, less the great lama high up on a golden throne and more the friendly counselor who speaks directly to us and shares his personal experience. In the same way, he makes meditation more accessible. “The main practice I try to maintain is to be mindful and aware in all my activities, whether it is moving about, sitting, lying down, or anything else. I think I do manage to maintain this practice of a moment-to-moment focus in my mind.” This, too, recalls another verse from the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva:

In brief, wherever we are and whatever we do, While staying continually mindful and alert To the state of our mind, To benefit others is the practice of a bodhisattva.

The Karmapa makes this activity seem simple and easy, but in truth this unwavering attention is the sign of a very advanced practice. If we add in the understanding that since the Karmapa is a highly realized being, he is continually aware of the nature of his mind, what he is actually describing is the state of a buddha.

In a similar way, the Karmapa gives deep teaching in a most casual way. He closed one of his talks by saying, “I do not think this was a fully authentic instruction for meditation, but you could say that I seemed to give a teaching and you appeared to listen to it.” After disparaging himself again, the Karmapa demonstrates with a living example how the duality of relative truth manifests as illusion— both subject (“I seemed”) and object (“you appeared to”) are mere appearance, emptiness inseparable from whatever is arising. Here the Karmapa gave simultaneously the illustrative context and the teaching about it.

For the receptive reader, these jewels can be found throughout the teachings in Canada. To make them more easily accessible, one quote from each teaching has been set at the beginning of its chapter. They are reminders of how the Karmapa has brought forth a profound message in simple and accessible language with an authenticity that connects him with everyone he meets as he opens out the treasures of Buddhism for modern times.

A Note about the Translation

Chapters Two to Five and Seven were originally translated by Tyler Dewar and the remaining six are the work of David Karma Choephel, who reviewed his translations. I listened to recordings of the Karmapa’s Tibetan and the translators’ English to adjust and edit the translations. The Karmapa’s initial greetings to the audience for each talk were similar enough that most were elided though one was left in place as an example, and the conclusions were also shortened on occasion. Except for the words in italics or other speakers who are clearly identified, the entire text is from His Holiness. If there are any errors or infelicities, the responsibility lies with myself alone and I apologize in advance for any mistakes that may have found their way into the text.

Michele Martin